The story of Rabbi Barbara Aiello is an inspiring example of perseverance, cultural identity, and dedication to faith. Born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, she became the first woman to serve as a rabbi in Italy, paving the way in a field traditionally dominated by men and in a country where Judaism still follows conservative models. Her journey is marked by new beginnings, challenges, and the realization of a dream that seemed unlikely when she was younger.

Barbara Aiello’s connection to Italy began long before she moved there permanently. In 1975, she made her first trip to the village of Serrastretta in the Calabria region, alongside her father, who had emigrated to the United States as a child. The trip had a special purpose: to return her father to his roots for the first time since his departure in the 1920s. Upon stepping foot in Serrastretta, Aiello felt something inexplicable, as if that place had a greater significance in her life.

“I remember looking at the hills, the stone buildings, and the way people greeted each other in the square and thinking, ‘One day, I’m going to live here,’” she recalls. The desire lingered for decades while she pursued her career in the United States. But, as the rabbi herself says, fate found a way to bring her back.

During her youth in Pittsburgh, Aiello never imagined she would one day become a rabbi. Coming from a traditional but not orthodox Jewish family, she was the first in her family to attend college. She studied to become a teacher and later ventured into the world of children’s entertainment as a professional puppeteer, a profession she held for 17 years.

Despite her love for teaching and the arts, she felt an inner restlessness, a calling that increasingly drew her closer to religion. In the era in which she grew up, the rabinate was a strictly male-dominated field – the first woman to be ordained as a rabbi in the United States, Sally Priesand, only received her title in 1972. When Aiello graduated in 1968, the possibility of a woman taking on such a role was virtually nonexistent.

“I always believed that it is a vocation, a divine calling,” she says. “But it was so far removed from my reality that, for a long time, I thought I was too old to start.”

It was a conversation with a rabbi that changed her trajectory. “He asked me how old I was. When I said I was 42, he replied, ‘How are you going to feel at 52 if you still haven’t done this?’” The question lingered in her mind until, at the age of 47, she decided to take a leap of faith. She entered seminary, and four years later, she was ordained as a rabbi by the Reform movement, which seeks to modernize Judaism and make it more inclusive.

Over the course of 25 years as a rabbi, she worked in synagogues in Florida, taught Hebrew in the Virgin Islands, and led projects aimed at progressive Jewish communities. Then, in 2004, an opportunity arose that would completely change her life: becoming the rabbi of the first Reform synagogue in Italy.

When she received the invitation to lead the congregation in Milan, Aiello knew she was facing a great challenge. Italian Judaism, predominantly orthodox, did not view the more modern branches of the religion favorably, and the idea of a female rabbi was unprecedented in the country. “In the beginning, there was resistance,” she admits. “Judaism in Italy is much more traditional than in the United States. While in the US, the Reform movement is the largest, in Italy, orthodoxy still predominates.”

In addition to the cultural and religious differences, adapting to the language was also an obstacle. Although she grew up hearing her father speak Italian, she realized her vocabulary was limited to everyday topics. “I thought I spoke fluently, but I discovered I didn’t know how to discuss deep topics or give sermons in Italian. I had to study a lot.” With the help of a tutor specializing in theology and psychology, she improved her language skills and gradually gained the trust of the community.

Two years after arriving in Italy, Aiello received another unique opportunity: to found a synagogue in Calabria. A couple whose wedding she had officiated decided to fund the project, and she saw it as a chance to settle in Serrastretta, the village that had always held a special place in her heart.

“Many people ask me why I chose Serrastretta to open a synagogue in Calabria. But, in truth, I think it was Serrastretta that chose me. My father was born here, my ancestors lived here. There was a natural connection.”

For the past 18 years, the synagogue has been a welcoming space for the local community and a point of reference for descendants of Jews from the region who seek to reconnect with their roots. During this time, Aiello also built a personal life in the town: she married her second cousin, Enrico, also Jewish, and became an integral part of the village’s social fabric. “Now, between the two of us, we’re probably related to almost everyone in the town,” she jokes.

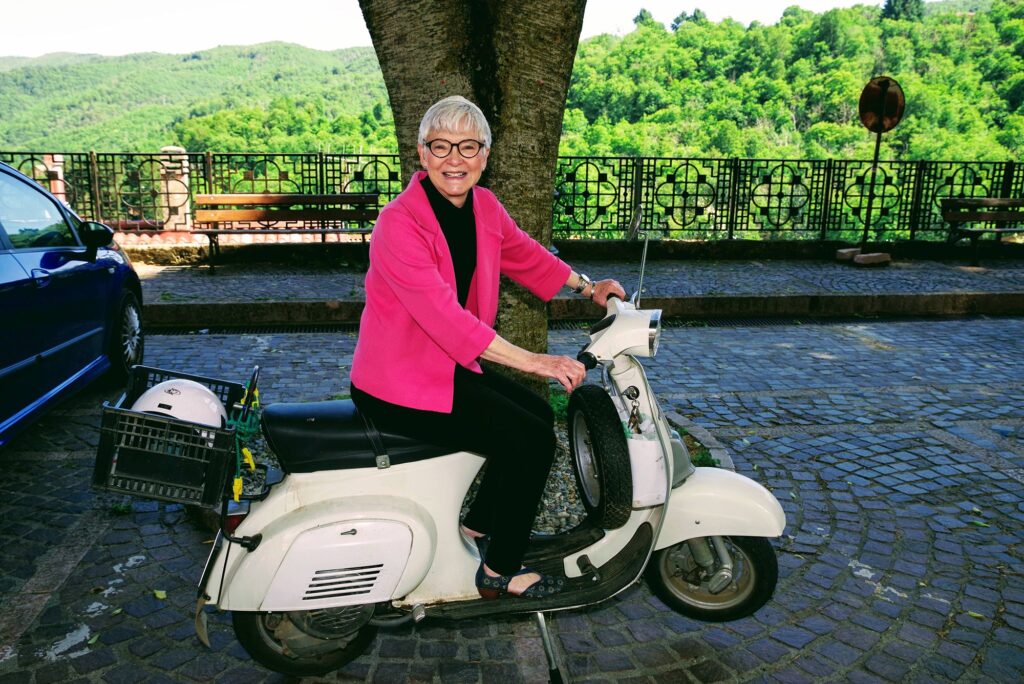

Today, at 77 years old, Aiello feels fully at home in Calabria. While she acknowledges the challenges of living in a village – such as the distance from major urban centers and limited access to healthcare services – she highlights the sense of community and human warmth as factors that make everything worthwhile.

She also emphasizes the cultural differences between the United States and Italy. “In the US, life revolves around work and productivity. Here, time is lived around the table, with family and friends. It’s a way of life that I’ve learned to appreciate.”

However, she admits that health concerns could be a deciding factor in the future. As a two-time cancer survivor, she needed to return to the United States for surgery, as she felt more secure in the American healthcare system. “If anything would make me return, it would be health. But for now, I’m happy here.”

Currently, Aiello continues to promote interfaith dialogue and works toward strengthening Jewish identity in Calabria. Her greatest wish is that her story inspires other women to follow their vocations, regardless of the barriers imposed by time, tradition, or circumstances. After all, as she likes to say, “There’s a word in Yiddish, beshert… It means ‘it was meant to be.’”